COVID-19 in modern Russian laughter discourse: psycholinguistic method of devaluation of danger as an effective method of psychological protection

COVID-19 в современном русском смеховом дискурсе: психолингвистический метод девальвации опасности как эффективный метод психологической защиты

Abstract

The mysterious Russian soul is always looking for non-trivial aspects of a problem. The modern coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) has become the subject of ridicule in the everyday laughing practices of Russian people. In this case, the laughing discourse acts as a form of psychological defense and struggle against the inevitable evil. The importance of the research is due to the lack of knowledge of the communicative and cognitive aspects of laughter discourse and the need to study the modern anecdote on the topic "coronavirus pandemic" in the aspect of forming the stability of the human psyche in the conditions of pandemics and isolation. The relevance of this work is also determined by the fact that it expands the empirical base of discourse linguistics, LSP theory and practice, motivology and emotive linguistics, whose interests include consideration of the problem of the influence of emotions on language. The relevance of the work also lies in the fact that special attention is paid to the little-studied phenomenon of "black humor", which is vividly represented in the laughing discourse about coronavirus. Unfortunately, today Russia occupies the leading positions in terms of the number of people infected with virus COVID-19. Archetypal fear of unknown Evil, of invisible death evoke chthonic experiences of the unconscious from the depths of the subconscious, actualizing the laughable techniques of devaluing danger as one of the effective methods of psychological protection. The world stereotype defines Russian people as frowning and unsmiling, extremely hostile to the world around them. The article reveals the specifics of modern Russian anecdotes about COVID-19. This allows the reader to understand what the stress resistance and resilience of the Russian person in a situation of degenerate press of negative information in various media is. This situation is complicated by fake news stories about the pandemic. What are Russian people laughing at during the pandemic? What helps them survive and stay mentally healthy in this situation? What is the specifics of Russian jokes about the pandemic? How do these anecdotes structure a person's inner space in a new way? What Parallels can we find in a laughing culture that plays up the stigmatized situations of tragedies, wars, and epidemics? This article is intended as an attempt to answer these and other questions.

Keywords

coronavirus (COVID-19), emotive linguistic, laughter discourse, Russian anecdote, Russian language pictures of the world, psycholinguistic.

Аннотация

Загадочная русская душа всегда в поиске нетривиальных путей решения проблемы. Современная пандемия коронавируса (COVID-19) стала предметом осмеяния в повседневной смеховой практике русских людей. В этом случае смеховой дискурс становится способом психологической защиты и борьбы с неизбежным злом.

Актуальность исследования обусловлена неразработанностью коммуникативно-когнитивных аспектов смехового дискурса на тему "пандемия коронавируса" в аспекте формирования устойчивости психики человека в условиях пандемий и изоляции. Актуальность данной работы определяется также тем, что она расширяет эмпирическую базу дискурсивной лингвистики, мотивологии и эмотивной лингвистики, в круг интересов которых входит рассмотрение проблемы влияния эмоций на язык. Актуальность работы заключается также в том, что особое внимание уделяется малоизученному феномену "черного юмора", который ярко представлен в смеховом дискурсе о коронавирусе.

К сожалению, сегодня Россия занимает лидирующие позиции по количеству людей, инфицированных вирусом COVID-19. Архетипический страх перед неведомым злом, перед невидимой смертью пробуждает хтонические переживания бессознательного из глубин подсознания, актуализируя смеховые приемы обесценивания опасности как действенный метод психологической защиты.

Мировой стереотип определяет русских людей как хмурых и неулыбчивых, крайне враждебно настроенных к окружающему миру, но это не так. Мы раскрываем специфику современных российских анекдотов о COVID-19. Это позволяет читателю понять, что такое стрессоустойчивость и жизнестойкость русского человека в ситуации разрушительного прессинга негативной информации в СМИ. Эта ситуация осложняется фейк-ньюнс о пандемии. Над чем смеются русские люди во время пандемии? Что помогает им выжить и оставаться психически здоровыми в этой ситуации? В чем специфика русских анекдотов о пандемии? Как эти анекдоты структурируют внутреннее пространство человека по-новому? Какие параллели мы можем найти в смеющейся культуре, которая воспроизводит стигматизированные ситуации трагедий, войн и эпидемий? Данная статья задумана как попытка ответить на эти и другие вопросы.

Ключевые слова

коронавирус (COVID-19), эмотивная лингвистика, смеховой дискурс, русский анекдот, русская языковая картина мира, психолингвистика.

Introduction

The history of the study of laughter discourse is correlated with the history of mankind, it goes back more than 2000 years. Scientists, since ancient times, have tried and are trying to get to the heart of this phenomenon. The category of comic is studied in various Sciences: philosophy, anthropology, Philology, linguistics, sociology, pedagogy, psychology, etc. The number of arguments about the nature of laughter only increases. It is a common view that there is no need to investigate the very nature of the ridiculous. Russian anecdote in the space of the Russian picture of the world is in the diffuse space between everyday communication and artistic speech. The response to the coronavirus pandemic fits into the standard of behavioral responses of the human psyche to a psycho-traumatic situation.

Many scientists and philosophers have repeatedly asked themselves and others why, where one sees something funny, the other finds no reason to laugh. As a rule, "conditions of historical, social, national and personal order" become the starting point for denoting a laughing situation (Propp, 1997). Thus, the attribution of a phenomenon to the funny, comical or unfunny, non-comical is based on an individual or social system of values.

The mass consciousness tries to escape from the situation of social doom in the conditions of a pandemic, and the mass media, because of commercial interest, fulfill any orders that bring them dividends, using PR methods of influencing the consciousness, plunging the confused and/or desperate person into virtual reality (Karabulatova et al., 2017; Khachmafova et al., 2017).

To date, there are no strict criteria for distinguishing between funny/ not funny, comical/ ordinary. because, according to Marina Zheltukhina, the ridiculous "being unreliable knowledge, i.e. opinion, is subjective" (Zheltukhina, 2000). At the same time, many researchers try not to focus on this question (at least publicly), or simply avoid indicating their own point of view when answering it (Bestayeva, 2006; Karabulatova, 2019; Sobkin & Lykova, 2018; Tarasenkov, 2014).

In the Russian Humanities, the appeal to the text as a source of psychological knowledge is based on the work of L. S. Vygotsky "Psychology of art" (2000). Following him, other psychologists (Sobkin & Lykova, 2018) analyze the structure of a work of art to recreate the artistic, cathartic experiences that it causes.

Clinical psychologists and psychotherapists note that a fifth of Russians (which is at least 20% of the Russian population) are predisposed to the activation of serious psychological problems after the end of the quarantine and the coronavirus pandemic (Petrov, 2020). In this regard, an anecdote about coronavirus can act not only as a means of resolving a psycho-traumatic situation, but also as a means of preventing post-traumatic stress disorder (Kopp, 2013).

Therefore, researchers come to the reasonable conclusion that the psychological mechanism of experience should be sought not in a specific individual, but in the text itself. This approach allows us to turn to the semiotic organization of the anecdote text as a source for the study of psychological experience:

- their own national identity (for example, Jewish, Armenian, Chinese, Ukrainian anecdotes, etc.);

- the preservation of their own psyche in conditions of self-isolation;

- reproducibility of social stability;

- sexual and matrimonial relations, etc. However, this goes back to the manipulative practices of public consciousness, which were spread thanks to the laugh culture of lubok (lubok is a so-called funny sheet, a type of naive graphics, folk art, an image with a signature, characterized by simplicity and accessibility of images, with an orientation towards commoners, was originally a type of folk art) and agitka (agitka - agitation poster, propaganda proclamation, combined elements of folk lubok, but was a simple literary work with an orientation on an actual socio-political topic, where all visual means are aimed at maximum impact on the reader/ listener) during the First world war (Karabulatova, 2020).

The challenging situation with coronavirus is played out in various aspects by the Russian people. as we can see from the examples, the anecdote acts as a laboratory where the aesthetics of verbal creativity is crystallized in its forms, creating a fruitful ground for "big" literature and art.

Materials and methods

Purpose of this article: to understand the nature of creating a laughing situation in Russian anecdotes about coronavirus COVID-19, which is due to the structural and semiotic analysis of the symbolic reality of the anecdote. The hypothesis is that the effect of ridicule is due to partial or complete changes in the semiotics of the sign. In this case, we observe psychological mechanisms for generating the experience of identity of both the addressee and the recipient of the joke.

An anecdote is always linked by an umbilical cord to a real fact. In our case, the coronavirus pandemic is this fact. The main events of the stories in the anecdotes about coronavirus may be fictional, but they are consistent with reality: it could have been.

The poetics of the modern anecdote is considered by researchers (Borodin, 2001; Chirkova, 1997; Vertyankina, 2001), but I consider the anecdote in a different plane. Anecdote about COVID-19 acts as a specific speech genre. as a component of the vast universe of everyday social and communicative interaction of our contemporaries. This immediately raises a series of questions:

How and in what communicative conditions does such an anecdote appear?

- Who is its Creator?

- The target audience of the joke?

- Where does it spread and function?

- What psychological mechanisms trigger the memory of a particular story?

A modern anecdote differs significantly from traditional anecdotes of the past because it is implemented in a rapidly changing social and information environment. I extracted anecdotes about coronavirus from the site of Russian-language jokes: https://www.anekdot.ru. Comparison of anecdotes of this site with anecdotes on the site of «Komsomolskaya Pravda» showed their identity. However, the site of Russian jokes showed a greater variety, and this fact predetermined the choice in its favor.

When I extracted it, I was guided by the coronavirus tag https://www.anekdot.ru/tags/коронавирус. In addition, any reader can see the relevance of a particular anecdote due to the ratings and ranking of anecdotes about coronavirus by popularity. In total, about 846 anecdotes about coronavirus were analyzed.

This site is also interesting because users leave comments on a joke. This makes it possible to track the social reaction to an anecdote.

The semiotic approach is implemented in this study and applied to the analysis of anecdotes, focusing on their sign nature, trying to explain the anecdote as a phenomenon of language (Levin, 1998; Lotman, 1973, 1974; Morris, 1968; Petrov, 1981). Anecdote acts as a complex whole formed by formal elements of different order. The structure of the anecdote becomes the source of meaning for this text. The structures underlying the anecdote are unconscious and objective, they exist independently of the observer, and they are constituted by differences and oppositions. From this point of view, we can analyze the structure of anecdote as a semiotic formation, studying the nature of anecdote as a cultural text.

Semiotic analysis of the anecdote leads us to identify the key semantic oppositions that set semantic conflicts in anecdotes about coronavirus.

Content-analysis of anecdotes studies essentially and structurally invariant anecdotes, which outwardly appears as a randomly organized and unsystematic text array.

Frame analysis of an anecdote about coronavirus is a method for studying the interaction of semantic and thought spaces of language, which allows us to model the principles of structuring and reflecting a certain part of human experience, knowledge in the values of language units, as well as ways to activate General knowledge that provides understanding in the process of language communication.

The discussion of the content aspects of various (from individual to social) identity problems in the anecdote about coronavirus is based on the idea of M. M. Bakhtin that "culture knows itself at the border" (Bakhtin, 1990). We also consider the use of psycholinguistic techniques in constructing an anecdote about coronavirus, based on the principles of text perception, namely:

- associative connections;

- phonosemantic level;

- use of polysemy;

- playing with phraseological units;

- use of hidden meanings;

- use of unplanned text integrity;

- the use of coherent, but not complete texts;

- the use of false attribution;

- the use of keywords;

- the use of communicative conflict;

- the use of barbs;

- the use of subcultures;

- the use of meta-anecdote principles.

The results of psycholinguistic tools allow us to give a more complete idea of the content of the concept, formed when studying the materials of lexicographic sources and text material.

Discussion

The reality that gives rise to the plot of the anecdote about the coronavirus COVID-19 fits into the General Canon, which states that the reality of the anecdote is a reality of a special kind, since it tends to the extreme, existential-laughing manifestations of being (Borodin, 2001; Podsiadlik III, 2014). For example: “I was walking in the Park and met a man who was talking to his dog. When I got home. he told me about it. We laughed with the cat for a long time afterwards!”

At the time, M. M. Bakhtin considered the laughing aspect of carnival culture, where he noted the peculiarity of the logic of "reverse"/ Vice versa, inside out/ shifter, when the movement "up - down", "dying-resurrection", "confirmation-denial" go constantly in opposite directions (Bakhtin, 1990). This feature is also pointed out by the British researcher E. Podsidlik III (Bergmann, 1999), who examines the language game and conflicts in the work of a literature teacher through essays and fiction. Using a literary anecdote of the English classics without involving samples of oral folk art does not allow you to track the mobile changes in the public consciousness of contemporaries, but it can give information about the life of society in a diachrony.

The experience of an anecdote is an excellent way to learn, on the one hand, the world of a “Stranger” in his “Friendliness”. On the other hand, it allows you to see your own "I" in this” Stranger”. Therefore, there is an awareness of their features in this “Stranger”, there is a sense of empathy for themselves and for this “Stranger”. For example: “The epidemic in Russia will end when talk shows start discussing Ukraine, not the coronavirus”; “The Chinese are darkness. Instead of holding a prayer service, they build hospitals in 10 days”; “We drink in an international company, I ask something from a German. Everyone was killed by the pole's phrase: “I'm a little afraid when the Russians and the Germans agree on something. The last time they did this, Poland disappeared after that, it was gone””; “Finally! The Armenians stopped being Italians due to the recent events on the pandemic in Italy!” etc.

E. M. Meletinsky rightly notes: "Anecdotes are created around the" stupidity / intelligence " axis. Stupidity is a set of violations of elementary logical rules, a paradoxical break in the natural relationship of subject, object, and predicate. Logical absurdity. widely presented in a variety of anecdotes" (Meletinsky, 2001). This clarification by E. M. Meletinsky is essential for understanding the basis of poetics and the existence of anecdote, because "absurd paradoxes are a specific feature of the anecdotal genre, and they, and not just joking or witty ending, determine its form" (Meletinsky, 2001).

The famous German psychotherapist N. Pezeshkian constructs his parables for the transformation of depressive conditions and psychosomatic diseases, using psycholinguistic techniques similar in the structure of the anecdote (Pezeshkian, 2010). The researcher acts as a medium through whose mouth the collective unconscious finds a voice and gives new opportunities "collect light hours in the dark" (Pezeshkian, 2010).

The focus of humor in psychotherapy is diverse. It is humor that helps resolve many internal and external conflicts without aggravating situations, so the importance of humor in psychological counseling and psychotherapy is reflected in the work of the annual conferences of the International Society for Humor Studies (ISHS). For example, so many research’s published in 2018 (Laineste & Fiadotava, 2018). Transforming In addition to ISHS, the Association for Applied and Therapeutic Humor (AATH) investigates productively and successfully the psychotherapeutic potential of humor on human health (Morrison, 2012). The Association provides scholarships for professionals and motivational speakers who apply therapeutic humor in their lives and work. The Association's management pays special attention to speakers who have overcome cancer. I think the coronavirus pandemic opens new possibilities for using humor for therapeutic purposes. I believe that examples of folk art in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic can be added to the psychotherapy protocols for the treatment of certain health problems of a person affected by coronavirus.

Some practitioners share the concepts of "therapeutic" and "non-therapeutic" humor. Thus, Bachelor A., Horvath A. (Bachelor & Horvath, 1999) rightly point out that psychotherapy can be successful only if the specialist has empathy, which is expressed in empathy, care, attention, and sincerity towards the patient. Cameron D. (Cameron, 2015) examines the verbal-paravertebral characteristics of conversational discourse. She pays special attention to the interpretation of the anecdote in this regard. Clinical psychologists define therapeutic humor as the deliberate and unexpected use of humorous techniques by psychotherapists, clinical psychologists, and other professionals to help clients/ patients better understand themselves and improve their psychosomatic health (Franzini, 2000).

L. D. Henman interviewed more than 60 former American prisoners of war who were kept in isolation, starvation, and torture in Vietnam for more than seven years, but they kept a healthy mind thanks to optimism and a sense of humor (Henman, 2001).

This method of dealing with difficult situations of wars and epidemics has long been known and popular. Just remember Boccaccio's “Decameron”, a masterpiece of laughter culture created during the plague in southern Italy. Laughter in the novels "Decameron" by Giovanni Boccaccio sounds fun, optimistic and life-affirming, despite the raging plague, extremely optimistic. According to researchers, this laughter symbolized the farewell to the dying middle Ages and the greeting of a new, humanistic society (Khlodovsky, 1985). This suggests a parallel with letting go of the industrial world. Another question is: what format of society is coming? With what values? Apparently, the answer is already there, but not announced. The energy of anticipation of the carnival, a kind of "feast during the plague" of the XXI century is accumulated in the modern anecdote about the coronavirus, echoing the behavioral traditions of the past, becoming the transforming energy of the inner picture of the human world. This idea is confirmed by an anecdote about the attitude of people to the modern pandemicCOVID-19:

“If we count the number of anecdotes, memes, and other jokes, then there has never been such a fun pandemic in the world”; or another:

“Corona is a great name for worldwide promotion, from a marketing point of view. It sounds almost the same in all languages of the world. And in all languages means something Royal, bright, Tzarist! And it becomes clear to everyone that the coronavirus is not a simple virus, there are billions of them. And The king is a virus! Scary! Not in Russia! We have a Tzar-gun that does not fire, A Tzar--bell that does not ring, A Tzar-virus that doesn't infect. And the Tzar does not reign, but just works every day”.

The works of B. Borcherdt (Borcherdt, 2002) can give a lot to understand the significance of humor in the mental health of modern people who have been subjected to long-term self-isolation and were in a long-term stressful situation of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Indeed, making the other person laugh is the main purpose of the joke. You can't disagree with A. Wierzbicka, that anecdote involves the participation of the listener: anecdote not only needs to be able to tell, but also to be able to read, and be able to listen (Wierzbicka, 1996). The culture of anecdote also implies a certain level of perception culture based on background knowledge and elements of the recipient's speech competence. Why, for example, does the American therapeutic humor Association train people to tell humor professionally? The answer to this question is in the work of A. D. Shmelev and E. Ya. Shmeleva, since the very telling of an anecdote is not a narrative, but a performance produced by a single actor (Shmeleva & Shmelev, 2002). In this case, both participants in the game situation of the joke must accept the terms of this game, then intra-genre interaction will take place within the genre scenario.

There is no doubt that humor is included in all types of social interactions, although researchers emphasize the playful nature of humor, but according to R. Martin, humor is focused on serious tasks in the field of external social, as well as internal cognitive and emotional functions. It is this set of functions that aims to improve relationships between people and relieve stress by laughing at threatening events, facts, conditions, and things (Martin, 2002).

Scientists and practitioners emphasize that humor focuses on positive aspects of life (Bergmann, 1999; Ivanova, 2008; Ivanova et al., 2014; Martin, 1989). When a person perceives the world through the prism of laughter and humor, he will always find something valuable and meaningful for himself in a difficult, unpleasant, stressful situation. Despite different approaches and interests, all researchers agree on one thing: anecdote acts as a way of understanding modern reality, defining some characteristic features of the existing situation.

Results

Today, all countries of the world are undergoing a radical transformation of spiritual, moral, and socio-economic life. Russia is no exception. Strict conditions of the quarantine regime, hyper-control, long-term isolation, powerful media pressure, deterioration of the life of ordinary citizens, whipping up the fear of death deform the human psyche to one degree or another. In this regard, people turn to a life experience that could save them not only physically, but also mentally. The culture of ridiculing danger has been known for a long time, but in Russia it has acquired new features due to the long confrontation with the West and the peculiarities of the mentality. The Russian laughter tradition has a feature that distinguishes Russian laughter culture from European laughter culture.

The Western European tradition comes from the setting "funny, and therefore, it is not terrible". At the same time, the Russian tradition is the opposite of this formula: "funny and scary at the same time." For example, in Russian culture, if a girl is overly made up, provocatively dressed, or has improved her plastic appearance beyond the accepted stereotypes in society, then those who give her a shout will say that she is terribly beautiful. Beauty and ugliness balance on a very shaky edge.

Also, the Russian culture of laughter includes oxymoronic features, the so-called "black humor". This "black humor" is related to Slavic paganism and witchcraft, so the laughter of a witch and / or sorcerer is creepy and terrible. In principle, Russian jokes about COVID-19 can be attributed to this cycle of jokes, because here we meet such anecdotes as: 1) sadistic jokes; 2) jokes about isolation-concentration camp; 3) jokes about dictators; 4) jokes-horror stories; 5) jokes about death.

- Sadistic anecdotes. This group of jokes is adjacent to the group of jokes about death. Since the coronavirus quickly spreads and mutates, while its symptoms remain completely unclear, any death during the pandemic in the anecdote is presented as a death due to the coronavirus. These anecdotes have semantic Parallels with common so-called "sadistic" nursery rhymes. As a rule, the story begins with a simple situation ("case at work", "dreams"). After a sharp change in the narrative and the fall of "black" humor in the stigmatized sphere ("violent death", "gang rape").

“-So, write: cause of death-coronavirus.

- Doctor, there was a gunshot ...

- Yes, it is a concomitant disease.”

“Fear the fulfillment of your desires!

Petrovich's old dream: Threesome or group sex, suddenly came true. When he sat down.”

“A very polite boy always gave way on public transport and kept a distance in the queue, so he pooped.”

- Jokes about isolation-concentration camp. Unlike other countries, Russia has not imposed a state of emergency, but has imposed a regime of self-isolation. The word isolation itself contains a pronounced negative connotation, which connects this concept associatively with the time of revolutions, wars, and total control. Hence, images of the politics of totalitarian States of the past and present occupy one of the key places in anecdotes about coronavirus.

“Each official has a concentration camp supervisor (vertukhai – in Russ argo)”

“The week of quarantine from March 28 to April 5 is best characterized by the title of the film "Holidays of strict regime"”

Putin: Pechenegs and Polovtsy.

People: Well, you would still remember what happened before our era!

Putin: The Spartans

- Jokes about dictators. This group of anecdotes is related to the previous one. However, self-isolation associatively evokes images of tough leaders of the past and present. The analysis of anecdotes of this group shows that, first place goes to Lenin, the second - Putin, third place - Kim Jong-Un, 4th place - trump, 5 - Merkel, 6th place - Hitler, 7 - Lukashenko. The image of Stalin occurs only once and then indirectly. We see parallel images of such rulers and images of hard States: North Korea, Sparta, tsarist Russia, Nazi Germany.

“In Germany, designers, freelancers and creative people are paid 5,000 euros during the quarantine period...Because Germany already knows very well what will happen... if a frustrated artist changes his profession...”

“Who in Moscow best observes the regime of self-isolation?

- Lenin in the Mausoleum.”

“Dialogue with my wife:

- Because of the virus, the Lenin mausoleum was closed.

- Lena, he won't get infected.”

“Donald Trump believes that Kim Jong-Un is more alive than dead”

“They used to think that Belarus was a dictatorship. And now this is the freest country in Europe-you want to walk on the street, you want to barbecue in nature, you want to go to football.... And Belarus will not get anything for it. After all, in Belarus, the son is not responsible for the father, since he does not choose Batska.”

“Coronavirus is a new Lenin. And his slogans are the same: "Long live the world epidemic!", " All power to the nurses!", " Land - to the peasants (who did not survive the coronavirus), hospitals-to the workers!»”

“- When will this pandemic end?!!

- In our country, as Putin says, so it will end...”

“Peskov said that Putin is a real expert in any case, and somewhere in the middle East, the Saudis smiled.”

- In Sparta, the sick were simply thrown into the abyss-said Putin.

Then he thought: This is an idea!

- Jokes-horror stories. If in children's horror stories the main character is a girl or a boy, then in horror stories the main character can be a single man, a single woman, or a cinematic hero (a zombie). Among modern children, oral horror stories have lost their appeal (Maryina & Sukhoterina, 2017). However, this topic is presented among the anecdotes. Perhaps this fact is because adults who compose horror stories have had the experience of living children's horror stories in their lives. Sometimes these anecdotes look like a kind of forecast of the situation, considering the past historical experience.

“International experience, in this case Chinese:

1958. The poor harvest of grain. The sparrows are to blame, the Pilot pointed out. Chewed up. To fly maybe 12 minutes and drops dead. The enemy is defeated!

1962. The crop was eaten by caterpillars. Starvation of millions.

2019. Coronavirus. Lives 14 days. The enemy is defeated!

2020. ???????”

“-What will You do if the pandemic continues for at least another five years?

-I'll retire!”

“It is good to live alone, no one interferes: if you want to go to the store, if you want to take out the garbage, if you want to die.”

The perception of an anecdote is designed for the effect of surprise, a kind of "short circuit" followed by a reboot. As a result, the recipient suddenly discovers all the absurdity depicted in the joke. For example:

“Two policemen over the body:

"Pull the pitchfork and axe out of his back, then run a rapid test. This coronavirus has gone wild!”; “In connection with the threat of the spread of the coronavirus, digital permits for sex will be introduced from May 12. To get permission to have sex with your wife, click on the number 1.to have sex with someone else's wife, click on the number 2. Attention! Before sex, make sure that your partner has digital permission”.

Anecdotes about coronavirus involve all levels of language to maximize the emotional and volitional sphere of a person. we will present the main types below.

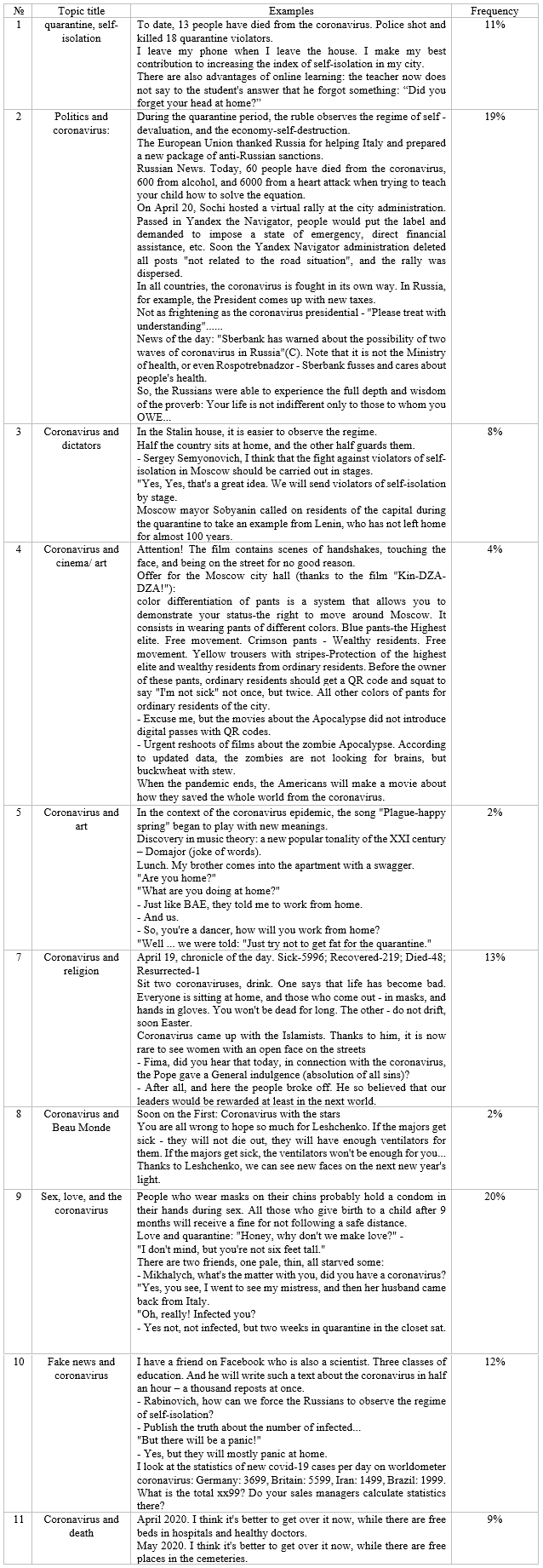

Table 1.

The main themes of Russian jokes about coronavirus.

The study of anecdotes faces the difficulty of creating a universal typology. Anecdote about coronavirus as a means of preventing post-traumatic stress disorder solves the following problems:

- mental pain;

- emotional dependence;

- being "here and there", that is, wherever a person is, he simultaneously seems to be in that traumatic situation all the time;

- problems of loneliness, despair, denial and avoidance;

- obsession;

- violation of the self-concept;

- violation of empathy, etc. (Leahy, 2019).

An anecdote is not always intended to make the recipient laugh. A smile, a grin, a grin, or just a meaningful exchange of glances can be a reaction to an anecdote.

Conclusions

The scientific novelty of the research is because the work for the first time gives a complete idea of the anecdote about coronavirus COVID-19 and its role in the public consciousness of the modern Russian person.

Increasing the power of information in a variety of media increases mental stress, so focusing on the usual things will reduce the level of anxiety, while the use of laughter eases internal tension, reducing procrastination and allowing you to stay healthy mentally.

The Russian anecdote about coronavirus reveals a deep connection with the folklore tradition, causing specific transformations of all artistic innovations and realities that penetrate from the outside.

This feature of the anecdote can be used in crisis conditions of the individual. At the same time, the list of areas of application of the anecdote about coronavirus is quite wide: offering ways to solve problems; helping to know oneself; increasing motivation; strengthening the heuristic of the psyche and the discovery of new ideas; increasing critical thinking and self-control; reducing resistance to change and transformation; openness to the new; building a new personal "I"; using built-in instructions; modeling constructive ways of communication; helping to discover recipients ' own internal resources; reducing the level of anxiety and phobias.

Acknowledgements

This study has been completed with the help of the financial support granted by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation under the Program of Increasing the Competitiveness of PFUR "5-100" among the world's leading scientific and educational center’s for 2016-2020.